Red Bull at 20

And then, almost out of the blue, van teams began rolling out in California, Texas, and New York. They were going to retailers, offering a sleek, but tiny silver and blue can that didn’t scream “radical.” In the center was a yellow circle with two wild animals charging at each other. The sales team called it an “energy drink” and anyone who tried it couldn’t deny that it delivered on that name; the stuff may not have tasted great but it sure gave you a buzz.

Impressed retailers sought to give the drink a chance, but then came the catch: the price point was $2 for an 8 oz. can and the salesmen wanted three facings and a sticker on the door. There would be no free cases handed out, money had to exchange hands, and the company wouldn’t pay slotting fees. No bottom of the fridge placement allowed, either. Today a no-name brand walking into bodegas, let alone chain stores, and making these demands sounds untenable. At the time, however, this brazen, strongarm strategy cemented Red Bull as the first and largest energy drink in the country and ultimately the world.

“If people said no, then we just said ‘That’s okay, you’re not ready for it yet, but we’ll be back,’” said Christopher Ustick, the executive vice president of Red Bull’s New York and New Jersey distributor The Beverage Works.

With a lineup of regular sports and record-breaking stunt events, the brand associated itself with the high octane worlds of extremophiles and landed priceless press coverage. Despite the premium retail price – and an even more ridiculous markup in nightclubs – Red Bull quickly swept through cities, college towns, sports clubs, and the suburbs to entwine itself into the culture as a household name in shockingly few years. Rumors spread, hospitalizations made headlines, and although to outsiders the brand’s often controversial press and incongruous adverts made it feel more like a bull in a china shop somehow rampaging its way to success, the actual story of how this niche drink rose to the top is a story of precise, aggressive, and daring sales and marketing techniques that turned Red Bull into an enigma in consumers minds.

Hailing from Austria, Red Bull first hit U.S. shores in 1997. In honor of its twentieth anniversary, BevNET spoke to several people associated with the brand in the early days to find out how the drink got off the ground.

THE BULL RING

Red Bull was invented in Thailand by Chaleo Yoovidhya and sold by his company TC Pharmaceuticals as a tonic for truck drivers and workers in need of extra energy during long shifts. Originally known as Krating Daeng, the “energy drink,” as it was called, drew its functional power from a blend of taurine, caffeine, and B vitamins. Much like Coca-Cola before it, Red Bull’s humble, medicinal beginnings, would quickly grow into an international phenomenon.

Krating Daeng was becoming well known in Thailand when, on a work trip during the early 1980’s, Austrian businessman Dietrich Mateschitz discovered the drink and instantly saw the product’s potential. He contacted Yoovidhya, and in 1987 he launched in Europe the company that would make the both of them two of the richest men in the world.

It would only be a brief 10 years before Red Bull launched in America, springing up on the West Coast with a bare bones staff in 1997. In 2000, operations opened up on the East Coast as well, and to many American consumers, the appearance of the drink on the market would feel like an overnight sensation; the result of years of careful planning.

When Peter Strahm joined Red Bull North America in 2000, as the Vice President and General Manager in New York, he thought his prior decade of experience in the beverage world would give him a sense for how the business might operate. Coming from tenures at PepsiCo, Snapple, and Jones Soda, he had a good spread of knowledge working with big and small brands, but Red Bull turned out to be a very different beast.

“The energy level was high, literally, but the weird part was that was internal,” Strahm told BevNET. “The external stuff we were dealing with was who the hell would buy an 8 oz. can of soda for a buck ninety-nine. It was an internal joke that everyone at Red Bull was drinking the water, but nobody else was.”

According to Strahm, one way to get the word out was to focus on the on-premise world of exclusive New York nightclubs. The brand was already an essential mixer in Europe’s infamous club scene, so it made sense to try a similar strategy stateside. If Red Bull attempted to be just another Coke or Pepsi competitor it may not have gotten far; instead, it became a lifestyle brand. Red Bull began by opening accounts with a few dozen bars throughout New York City, L.A., Boston, and Philadelphia. Bartenders could sell Red Bull and Vodkas at high markups, with some clubs charging as much as $18 for a single drink, Strahm said. But the word spread, and the speedball of upper and downer became the source of many unforgettably forgotten nights throughout the party scene.

“The number one issue they would have is people trying to pass off fake stuff for Red Bull,” Strahm said. “Rarely, do I ever see now someone asking for Monster and vodka. Red Bull becomes the core item, and all the liquor becomes the mixer. What brand do you know that’s able to do that and the reason why is they stuck to what made them great.”

Bruce Trent, Red Bull’s vice president of national accounts and off-premise sales from 1997 to 2006, said Red Bull was incredibly strict about entering all markets as on-premise only to begin in order to set the brand’s price point. They would start by penetrating the hot nightclubs to “get the crowd hooked on paying the higher retail” before strategically focusing on a handful of key convenience chains near colleges and other consumer hotbeds and offering early exclusives.

Ken Tenace, the company’s field sales manager from 1999 to 2005, started on the West Coast in Los Angeles. In the first few months the team might high-five each other for selling 10 cases in a day, he said. But within a few months the van team built a network and they would go from 10 cases to 100 to 1000.

“This was all before Monster launched, before Rockstar,” Tenace said. “We were just trying to create this category called energy drinks. People didn’t understand what energy was. You were doing more educating on that than on what Red Bull was.”

While the store had to honor their contract with the major CSDs, Red Bull’s success as an independent company eventually helped push a change to the way stores arranged their coolers, Tenace said. Many retailers now feature mixed-brand coolers, largely as a means to find top placement for independent energy drinks.

As Red Bull evolved and its name spread, imitators soon began popping up. Tenace recalled collecting as many as he could, eventually hoarding more than 500 cans of different drinks in his office, the vast majority now defunct today.

But in 2002, Monster Energy Drink premiered and began giving Red Bull a serious run for its money, sometimes stealing big accounts out from under them. When this happened, Strahm said there was a strategy for getting customers to fall in line: The Bull Ring. In one instance, he recalled Monster getting into a major Las Vegas hotel and pushing Red Bull out. Rather than take the loss, Red Bull got to work stirring up some envy by getting placement in every location around that hotel. Consumers who wanted Red Bull would end up taking their business across the street, ultimately forcing the loss onto businesses.

“We would call it bull ringing and figure that if that location doesn’t want us then every other bar and every other hotel around is going to have it,” Strahm said.

MARKETING & MURKETING

In 2002, writing for Outside, journalist Rob Walker observed Red Bull’s vague, Rorschach-style marketing strategy. Remarking that it the brand’s slogans and promotions appeared to deliberately obscure what the product actually was, he dubbed this approach “Murketing” and called the brand identity “nebulous” despite it having an identifiable target audience of athletes, nightclubbers and students.

“You could argue that what Red Bull drinkers have in common is a taste for the edgy and faintly dangerous,” Walker wrote. “But what does this really mean? Obviously any attempt to articulate such a thing would immediately destroy it. The great thing about a murky brand is that you can let your customers fill in all the blanks.”

Walker was certainly on the right track in his analysis. Part of the beauty of Red Bull as a brand was its mystique, Strahm said, and there was a deliberate vagueness in all of its promotions.

Much of this came in the form of Red Bull’s famous slogan: “It Gives You Wings.” Strahm said the catchphrase worked so well because it could mean different things to different people, something TV spots could capitalize on. For some, “wings” meant energy, for others creativity, some people even called the company to complain that it didn’t physically make them grow wings. But most of all it was just a good catchphrase that combined with a noticeable buzz from caffeine and sugar, made the brand name stick.

“You may not have even known what the brand was, but I don’t know a person today in the United States who can’t tell you ‘Red Bull Gives You Wings,’” Strahm said. “Every single person from an old person to a young person can tell you that. It’s sort of like ‘Just Do It’ for Nike. It’s one of those things that is iconic enough because the phrase is so inclusive to what the brand is.”

But perhaps what built Red Bull’s mystique most of all was the way the company turned fears and rumors that grew around it into momentum. Reports of health dangers, questions about ingredients’ effects, even word-of-mouth that the drink’s recipe contained substances harvested from real bulls quickly made their way through school dorms and into news articles. But rather than try to stamp out the negative press and do damage control, Red Bull saw fit to let the rumors spread, although Trent said the brand never actively fueled them. Nicknames for the drink like “Liquid Cocaine” and story after story of college students blacking out on Red Bull cocktails were effectively free advertising, especially in cities where on-premise sales from college kids reigned. According to Trent, buyers would occasionally raise concerns over the rumors they had heard, but business was moving so quickly they were never deal breakers.

OPEN FIELD

In her book Different: Escaping the Competitive Herd, Harvard Business School professor Youngme Moon highlighted the Red Bull’s strategy as an example of a “hostile” brand that, much like its sales team exemplified, told wary consumers to take their money elsewhere. Like a cartoon PSA drug pusher might say, you were either cool or Red Bull was just too much for you to handle.

“To be this inflexible requires a commitment to being unresponsive to consumer concerns, to being intransigent to market feedback,” Moon wrote. “The payoff, in other words, is brand differentiation to the extreme.”

One advantage Red Bull had in its first few years in the U.S. was that it was the only energy drink on the market. Typically, more time would be spent explaining the energy concept to buyers than explaining Red Bull, Tenace said. It took today’s next largest energy drink brands, Rockstar and Monster, until 2001 and 2002, respectively, to hit the market, and at around the same time the major CSD brands tried to get in on the game. In 2000, Pepsi acquired SoBe and began pushing Adrenaline Rush, and The Coca-Cola Company had KMX in 2001.

Red Bull’s resistance to outside pressure fit nicely into its stampeding brand identity. One of the few times the company made decisions based on competition was when it introduced a larger 12 oz. slim can size in response to the rise of other energy drinks that came in 16 oz. cans at the same price point, Ustick said. The new can, he said, looked like a 16 oz. can on the shelf, but still carried its premium image. Today, the 12 oz. is the top selling SKU in many markets.

TO THE EXTREME

Publicity stunts and athletic competitions have been a part of the Red Bull brand since 1988 when the Austrian branch of the company began the Red Bull Dolomitenmann, an intense relay event including mountain running, biking, paragliding, and kayaking. In the years since, the brand found new ways to get involved in sports, from owning football clubs in Europe to sponsoring kite sailing expeditions to Cuba. As a business technique, the events were and are prime brand exposure territory.

“We’d take the event and we’d make that a bonfire,” Trent said.

Whenever Red Bull hosted an event, such as their annual Flugtag, the company would reach out to every retailer and on premise account in area surrounding the event to participate in the publicity, Trent said. More remote events, such as those taking place in remote regions deserts, could also be a good means of getting Red Bull featured on TV in the days before going viral on social media was a prime means of building a brand.

TOMORROW AND TODAY

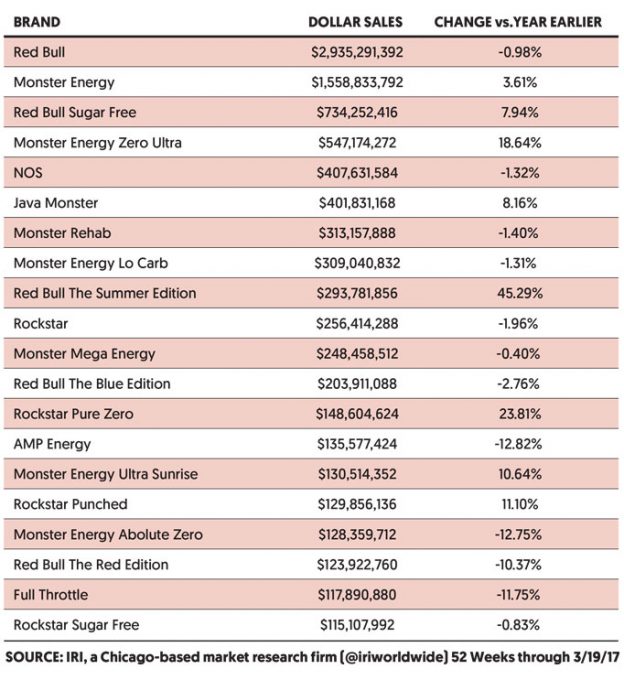

While Monster can sometimes outsell Red Bull in the U.S., the brand is still the number one energy drink worldwide, with few signs of that title slipping away. But according to analyst Howard Telford at Euromonitor, even as the energy category has been entrenched, that doesn’t mean there aren’t outside challenges that could chip into Red Bull’s bottom line.

The wellness wave of consumers looking for better-for-you beverages may prove to be a big challenge to the energy category. According to Telford, Red Bull’s main competition currently is more likely to be coming from products like functional waters and innovation in ready-to-drink coffee.

And even though Red Bull is now a household name, it still struggles with some of the same consumer hesitations it had back in the ‘90s.

“Believe it or not I still hear the same things I heard 15 years ago,” Ustick said. “We have older buyers who still have a negative connotation toward energy drinks. There’s still people out there who thinks it kind of faddish or doesn’t fit into their business.”

But 20 years in, Red Bull still remains the face of premium energy drinks, from its physical image (with its slimline can becoming something of an icon) to its brand aesthetic. Much can be learned from the way this billion dollar company built itself from the ground up to create one of the largest beverage categories today, but it can never be done the same way again.

Receive your free magazine!

Join thousands of other food and beverage professionals who utilize BevNET Magazine to stay up-to-date on current trends and news within the food and beverage world.

Receive your free copy of the magazine 6x per year in digital or print and utilize insights on consumer behavior, brand growth, category volume, and trend forecasting.

Subscribe